A brief commentary on classical music—its history, perception, and decline in relevance…

The term classical music itself is misleading. While it technically refers to music composed during the Classical period (approximately 1750–1820), it has become an umbrella term encompassing works from the Baroque, Romantic, and 20th-century periods, all the way to living contemporary composers.

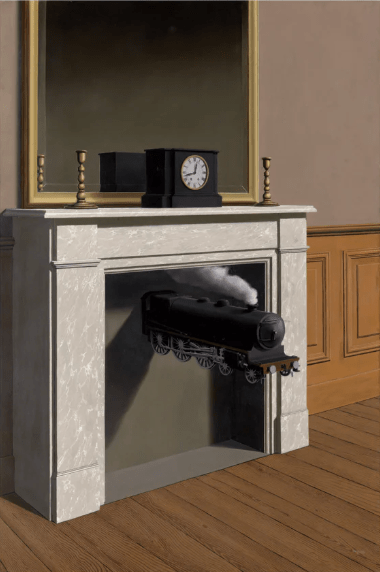

Analogous to physical art, classical music has experienced an evolution, with new composers attempting to break the form, gaining popularity, and giving rise to new eras.

Much of my personal listening focuses on Romantic-era composers such as Chopin and Tchaikovsky, characterized by lush melodies and mastery in the technique of tension and release (tension is built by using musical elements—such as dissonance, dynamics, tempo—that create instability or unrest, while release is the resolution of that tension, providing a feeling of satisfaction.) Their influence extends beyond the classical scene and into pop music. For instance, the chorus of Eric Carmen’s All by Myself borrows directly from the second movement of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18.

It’s precisely these memorable and incredibly beautiful melodies that perpetuates a renewed appreciation for the genre and encourages musicians to take passion in what they do. However, today’s contemporary composers have a reputation similar to avant-garde modern art for its experimentalism (take a listen to Phillip Glass’ opera: Einstein on the Beach). In particular, many of these pieces lean heavily into dissonance/atonality which can be hard on the ears for the general public.

Nonetheless, contemporary classical music has lots to offer. Composer Max Richter is one of my favorites, featuring soothing, easy-to-digest chord progressions (check out “On the Nature of Daylight”). Additionally, many professional orchestras opt to include contemporary works into their repertoire helping boost exposure.

However, a better way to promote classical music in my opinion is to compose film music. While film music has its roots in classical (i.e., Stravinsky, Korngold, Prokofiev, Shostakovich), many believe that it has branched far enough to be considered its own genre. Regardless of this ongoing debate, composers such as Hans Zimmer, John Williams, and Ludwig Göransson break into the mainstream by crafting breath-taking soundtracks using their classical training and expertise on music theory. A personal favorite of mine is Joe Hisaishi’s ‘One Summer’s Day’ from the movie Spirited Away, of which I had the privilege of playing in my symphony orchestra. Music from film, I believe, ultimately makes orchestra performances much more accessible and enjoyable.

While I wouldn’t go as far as to say that it’s in a death spiral, the classical performing arts are certainly at risk. One look at a concert hall and you’ll see one of the oldest cohorts for a performing arts audience. Hindering accessibility further includes the formal attire and concert etiquette—for example, clapping between movements isn’t a good look. For those who listen to the music, or are directly involved in its creation, I often observe that it can make people feel more sophisticated or intellectually elevated. This prestige attached to experience only gates the community, upholding stereotypes that present classical music as an archaic art form reserved for old snobby elites in the process.

Another factor complicating its accessibility is its hard-to-remember nomenclature. For example, one composer’s Symphony No. 7 in A major can be easily confused with another composer’s piece. Add in Opus numbers and then there are different movements within pieces… it takes a lot just to understand how to find & talk about classical songs.

But the overall decline in classical music can be simply attributed to the changing of the times—and the industry and institution’s refusal to adapt. So, I’ll return to composition of film music, which presents itself as a promising next step in the form’s evolution.

Magritte, René. La durée poignardée (Time Transfixed). 1938, oil on canvas, 147 × 98.7 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago

Leave a comment